Charter City

Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo

San José (Costa Rica)

curated by Maria José Chavarria

San José (Costa Rica)

curated by Maria José Chavarria

Aug to Sept 2012

Solo Show

Solo Show

Vallecillo vs Haussmann (in the tropics)

Charter City, the “model city” project with its own laws and form of government that has been recently admitted in the Honduran Congress could have been an extreme example in the chapter Haussmann in the tropics by Mike Davis. In a review of urban processes in which the state intervenes in favor of foreign investors, landowners, and local elites, he states: “As it happened in the Paris of 1860, under the fanatic reign of Baron Haussmann, the current urban development still struggles to combine the maximum private bene t with the maximum social control.”1 At the height of spatial segregation, the model city extends privatization to the whole urban territory and its social relations, which is a challenge to the very notion of city.

In City Charter, the exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design of Costa Rica, we are faced with the conditions that make possible the implementation of model cities or (bad) banana companies. In opposition to the “devastating- artist”2 gure embodied in the Baron Haussmann, I would like to see the proposal of Adam Vallecillo from the author’s idea as a constructor, understood here from the perspective of the occupation, his materials, tools, and processes. It is not rare to nd in the works of Vallecillo levels, carpenter’s clamps, bolts, and carpenter meters. The choice of the object has to do with its meanings, but also with the physical properties and the relations it is involved with. Often, he proposed a distorted use of the object that suddenly disconnects from the instrumental rationality to participate in other logics, as for example the carpenters’ clamp that does not gag other than its peers Misantropía (Misanthropy).

Transforming the metaphor into raw material, that yearning of Cildo Meireles also implemented byAdam Vallecillo, is one of the main successes of his work. That is why I prefer to enter City Charter through its materiality and referring an example; in Segmentario (Segmental) scrap tires patched and lled with valves are grouped together.These devices allow us to open and close, connect and disconnect, modulate or isolate the ow of liquids or gases; they become an almost ominous presence in the pieces of Vallecillo. If the valve is one of the essential monitoring tools in the industry, its proliferation in small sections is truly disturbing.

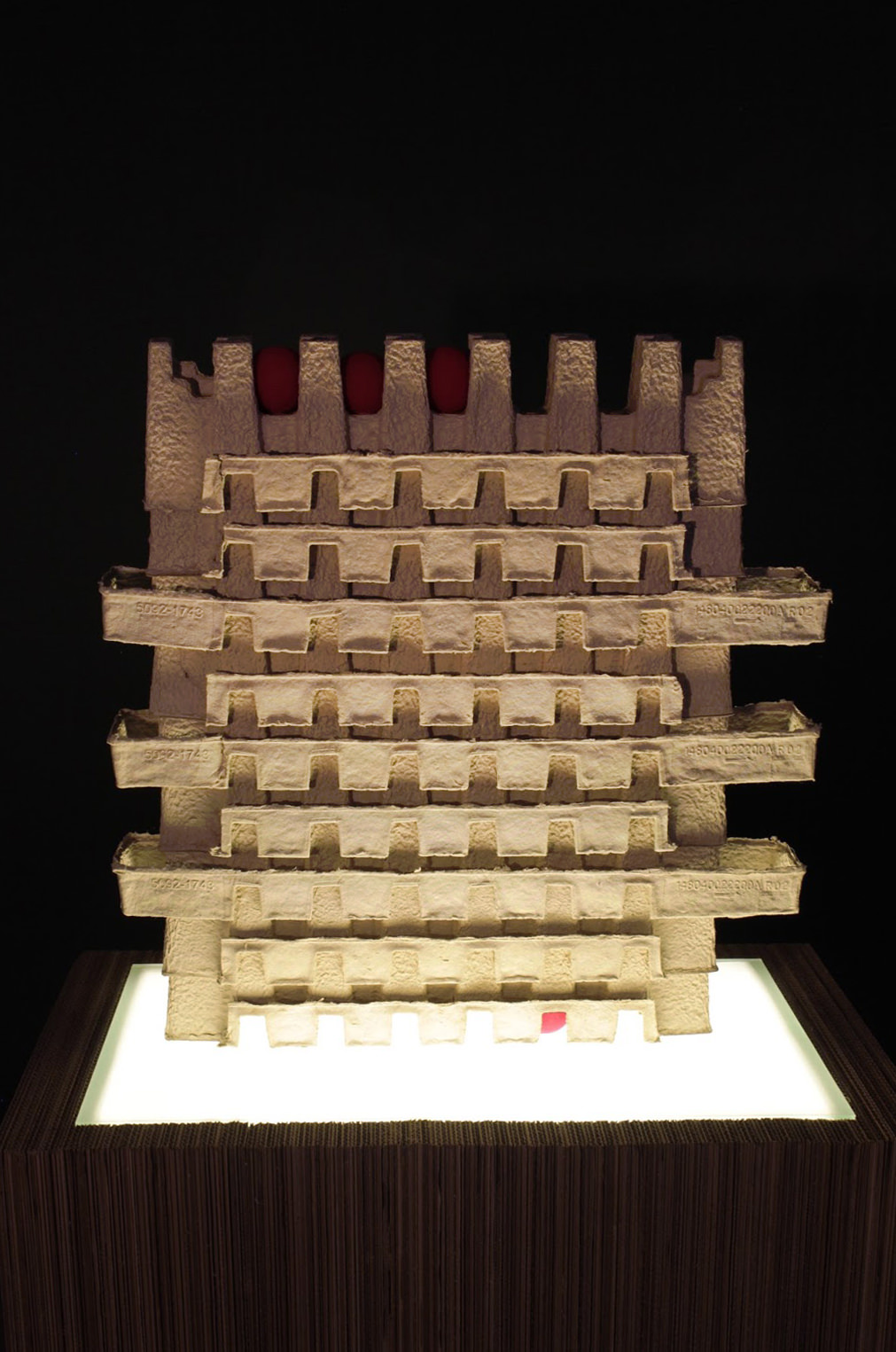

The work with manufactured industrial matter points out the dependency relation towards industrialized countries, while operating on the physical properties and the common uses of the material. The expanded polystyrene, for example, used as thermal insulation, works as refrigerator in Cuba Libre (Free Cuba) and as a constructive basis in Hipérbole (Hyperbole).

In City Charter, the exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design of Costa Rica, we are faced with the conditions that make possible the implementation of model cities or (bad) banana companies. In opposition to the “devastating- artist”2 gure embodied in the Baron Haussmann, I would like to see the proposal of Adam Vallecillo from the author’s idea as a constructor, understood here from the perspective of the occupation, his materials, tools, and processes. It is not rare to nd in the works of Vallecillo levels, carpenter’s clamps, bolts, and carpenter meters. The choice of the object has to do with its meanings, but also with the physical properties and the relations it is involved with. Often, he proposed a distorted use of the object that suddenly disconnects from the instrumental rationality to participate in other logics, as for example the carpenters’ clamp that does not gag other than its peers Misantropía (Misanthropy).

Transforming the metaphor into raw material, that yearning of Cildo Meireles also implemented byAdam Vallecillo, is one of the main successes of his work. That is why I prefer to enter City Charter through its materiality and referring an example; in Segmentario (Segmental) scrap tires patched and lled with valves are grouped together.These devices allow us to open and close, connect and disconnect, modulate or isolate the ow of liquids or gases; they become an almost ominous presence in the pieces of Vallecillo. If the valve is one of the essential monitoring tools in the industry, its proliferation in small sections is truly disturbing.

The work with manufactured industrial matter points out the dependency relation towards industrialized countries, while operating on the physical properties and the common uses of the material. The expanded polystyrene, for example, used as thermal insulation, works as refrigerator in Cuba Libre (Free Cuba) and as a constructive basis in Hipérbole (Hyperbole).

But, in each case, I establish different relationships with the same element: if the rst condition makes me notice its impermeable condition, the second emphasizes its lightness. Then, I see the tall buildings of foam topped with steel watches and I wonder the reason for having a model city here. The polystyrene responds with its ability to absorb impacts.

The increasingly sharp boundary between violent and safe places aggravates the social and spatial segregation. At the same time, the city of people and common good is relegated by public policies aimed only at producing and guarding private spaces. The safe city, that of condos and urban developments, is set in walled spaces, electronic monitoring devices, and private security guards. Monografía (Monograph) records a long sequence of labels of security companies in Tegucigalpa and Masterguetto piles locks attached to the same xed column, as a super uous resort for protection. The risk appears as a structural condition and not as an anomaly.

The disorder of the space-time measurement has a poetic and critical ef ciency in the work of Adán Vallecillo. In the piece that gives the exhibition its title, an extensive carpenter tape meter curves into space. City Charter is con gured as an inaccurate system rather arbitrary, incapable of accounting for reality. Given the failure of the measurement, the meters are armed with telescopic mirrors at the ends. Like a prosthetic optical measurement instrument, the re ection continues where the view is not enough. This similar dislocation suggests Tres tristes trópicos (Three Sad Tropics) with palm trees atop a hydraulic platform.

The sample is formed, nally, in the tension between the abstract space and the everyday object. As for me, I understood the enormous power of this work of Adam Vallecillo to think of the conditions of the city through Henri Lefebvre. The abstract space –the Marxist philosopher says- matches with capitalism and its urban planning and homogenization codes of experience. In the works of Adam, the abstract space is both present in the same con guration and denied by objects with memory, debris, traces of lived experience, all that which rejects the normative order or the rational homogeneous space. Thus, the city proposed by the constructor artist is also an area of struggle, as perhaps advertised by the bugs with valves or the Atari piece, whose title refers to the Japanese word that, in the game of go- warns the opponent that a dangerous move has been made.

by Tamara Díaz Bringas, 2012

1 Mike Davis, Planeta de ciudades miseria, Foca, Madrid, 2007, p. 136.

2 “My titles? I have been selected as the “devastating-artist”, Haussman quoted by Walter Benjamin, Libro de los Pasajes, Akal, Madrid, 2007, p.154.

The increasingly sharp boundary between violent and safe places aggravates the social and spatial segregation. At the same time, the city of people and common good is relegated by public policies aimed only at producing and guarding private spaces. The safe city, that of condos and urban developments, is set in walled spaces, electronic monitoring devices, and private security guards. Monografía (Monograph) records a long sequence of labels of security companies in Tegucigalpa and Masterguetto piles locks attached to the same xed column, as a super uous resort for protection. The risk appears as a structural condition and not as an anomaly.

The disorder of the space-time measurement has a poetic and critical ef ciency in the work of Adán Vallecillo. In the piece that gives the exhibition its title, an extensive carpenter tape meter curves into space. City Charter is con gured as an inaccurate system rather arbitrary, incapable of accounting for reality. Given the failure of the measurement, the meters are armed with telescopic mirrors at the ends. Like a prosthetic optical measurement instrument, the re ection continues where the view is not enough. This similar dislocation suggests Tres tristes trópicos (Three Sad Tropics) with palm trees atop a hydraulic platform.

The sample is formed, nally, in the tension between the abstract space and the everyday object. As for me, I understood the enormous power of this work of Adam Vallecillo to think of the conditions of the city through Henri Lefebvre. The abstract space –the Marxist philosopher says- matches with capitalism and its urban planning and homogenization codes of experience. In the works of Adam, the abstract space is both present in the same con guration and denied by objects with memory, debris, traces of lived experience, all that which rejects the normative order or the rational homogeneous space. Thus, the city proposed by the constructor artist is also an area of struggle, as perhaps advertised by the bugs with valves or the Atari piece, whose title refers to the Japanese word that, in the game of go- warns the opponent that a dangerous move has been made.

by Tamara Díaz Bringas, 2012

1 Mike Davis, Planeta de ciudades miseria, Foca, Madrid, 2007, p. 136.

2 “My titles? I have been selected as the “devastating-artist”, Haussman quoted by Walter Benjamin, Libro de los Pasajes, Akal, Madrid, 2007, p.154.

Vallecillo vs Haussmann (en los trópicos)

Charter City, el proyecto de “ciudad modelo” con su propia legislación y forma de gobierno que ha tenido reciente acogida en el congreso hondureño, podría haber sido un ejemplo extremo en el capítulo Haussmann en los trópicos de Mike Davis. En una crítica de procesos urbanos en los que el Estado interviene en favor de inversores extranjeros, propietarios de terrenos y élites locales afirma: “Como sucedía en el París de 1860, bajo el fanático reinado del barón Haussmann, el desarrollo urbano actual todavía se esfuerza para simultanear el máximo beneficio privado con el máximo control social”.[1] Colmo de la segregación espacial, la ciudad modelo extiende la privatización a todo el territorio urbano y sus relaciones sociales, lo que supone un reto a la noción misma de ciudad.

Charter City, la exposición en el Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo de Costa Rica, nos enfrenta a las condiciones que hacen posible la implantación de ciudades modelo o (malas) compañías bananeras. En oposición a la figura del “artista-demoledor”2 encarnada en el barón Haussmann, me gustaría pensar la propuesta de Adán Vallecillo desde la idea del autor como constructor, entendido aquí desde el oficio, sus materiales, herramientas y procesos. No es raro encontrar en las obras de Vallecillo niveles, prensas sargento, cerrojos, metros de carpintero. La elección del objeto tiene que ver con sus significados, pero también con las propiedades físicas y las relaciones en las que entra. Muchas veces propone un uso desviado del objeto que de golpe se desconecta de una racionalidad instrumental para participar en otras lógicas, como en el ejemplo de unas prensas sargento que no amordazan más que a sus iguales (Misantropía).

Transformar la metáfora en materia prima, ese anhelo de Cildo Meireles que Adán Vallecillo también pone en práctica, es uno de los principales aciertos de su trabajo. Por eso prefiero entrar a Charter City por su materialidad y por un ejemplo: en Segmentario se agrupan trozos de neumáticos parcheados y llenos de válvulas.

Charter City, la exposición en el Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo de Costa Rica, nos enfrenta a las condiciones que hacen posible la implantación de ciudades modelo o (malas) compañías bananeras. En oposición a la figura del “artista-demoledor”2 encarnada en el barón Haussmann, me gustaría pensar la propuesta de Adán Vallecillo desde la idea del autor como constructor, entendido aquí desde el oficio, sus materiales, herramientas y procesos. No es raro encontrar en las obras de Vallecillo niveles, prensas sargento, cerrojos, metros de carpintero. La elección del objeto tiene que ver con sus significados, pero también con las propiedades físicas y las relaciones en las que entra. Muchas veces propone un uso desviado del objeto que de golpe se desconecta de una racionalidad instrumental para participar en otras lógicas, como en el ejemplo de unas prensas sargento que no amordazan más que a sus iguales (Misantropía).

Transformar la metáfora en materia prima, ese anhelo de Cildo Meireles que Adán Vallecillo también pone en práctica, es uno de los principales aciertos de su trabajo. Por eso prefiero entrar a Charter City por su materialidad y por un ejemplo: en Segmentario se agrupan trozos de neumáticos parcheados y llenos de válvulas.

Esos dispositivos que permiten abrir y cerrar, conectar y desconectar, modular o aislar el flujo de líquidos o gases, devienen una presencia casi ominosa en las piezas de Vallecillo. Si la válvula es uno de los instrumentos de control esenciales en la industria, su proliferación en pequeñas secciones resulta verdaderamente inquietante.

El trabajo con materia manufacturada apunta la relación de dependencia hacia los países industrializados, al tiempo que opera sobre las propiedades físicas y los usos comunes del material. El poliestireno expandido, por ejemplo, que se utiliza como aislante térmico, funciona como nevera en Cuba Libre y como base constructiva en Hipérbole. Pero en cada caso establezco relaciones distintas con el mismo elemento: si el primero me hace notar su condición impermeable, el segundo resalta su levedad. Veo entonces los altos edificios de espuma coronados por relojes de acero y me pregunto las razones de una ciudad modelo aquí. El poliestireno responde con su capacidad de absorción de los impactos.

La frontera cada vez más tajante entre lugares seguros y lugares violentos agrava la segregación espacial y social. Al tiempo la ciudad de la gente y del bien común queda relegada por políticas públicas sólo dedicadas a producir y custodiar espacios privados. La ciudad segura, la de condominios y urbanizaciones, se configura en espacios vallados, dispositivos electrónicos de control y vigilantes privados. Monografía registra una larga secuencia de rótulos de empresas de seguridad en Tegucigalpa y Masterguetto amontona candados sujetos a una misma columna inamovible, como un superfluo recurso de protección. El riesgo aparece así como condición estructural y no como anomalía.

by Tamara Díaz Bringas, 2012

1 Mike Davis, Planeta de ciudades miseria, Foca, Madrid, 2007, p. 136. 2 “¿Mis títulos?... Yo he sido elegido como el artista-demoledor”, Haussmann citado por Walter Benjamin, Libro de los Pasajes, Akal, Madrid, 2007, p.154.

El trabajo con materia manufacturada apunta la relación de dependencia hacia los países industrializados, al tiempo que opera sobre las propiedades físicas y los usos comunes del material. El poliestireno expandido, por ejemplo, que se utiliza como aislante térmico, funciona como nevera en Cuba Libre y como base constructiva en Hipérbole. Pero en cada caso establezco relaciones distintas con el mismo elemento: si el primero me hace notar su condición impermeable, el segundo resalta su levedad. Veo entonces los altos edificios de espuma coronados por relojes de acero y me pregunto las razones de una ciudad modelo aquí. El poliestireno responde con su capacidad de absorción de los impactos.

La frontera cada vez más tajante entre lugares seguros y lugares violentos agrava la segregación espacial y social. Al tiempo la ciudad de la gente y del bien común queda relegada por políticas públicas sólo dedicadas a producir y custodiar espacios privados. La ciudad segura, la de condominios y urbanizaciones, se configura en espacios vallados, dispositivos electrónicos de control y vigilantes privados. Monografía registra una larga secuencia de rótulos de empresas de seguridad en Tegucigalpa y Masterguetto amontona candados sujetos a una misma columna inamovible, como un superfluo recurso de protección. El riesgo aparece así como condición estructural y no como anomalía.

by Tamara Díaz Bringas, 2012

1 Mike Davis, Planeta de ciudades miseria, Foca, Madrid, 2007, p. 136. 2 “¿Mis títulos?... Yo he sido elegido como el artista-demoledor”, Haussmann citado por Walter Benjamin, Libro de los Pasajes, Akal, Madrid, 2007, p.154.